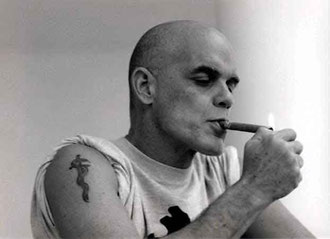

PEDRO JUAN GUTIERREZ

"I'm not interested in the decorative, or the beautiful, or the sweet, or the delicious... Art only matters if it's irreverent, tormented, full of nightmares and desperation. Only an angry, obscene, violent, offensive art can show us the other side of the world, the side we never see or try not to see so as to avoid troubling our consciences."

The streetwise gustiness of Bukowski and Miller pervades Cuban poet Gutiérrez's raunchy, symbolic, semi-autobiographical debut novel of life in 1990s Havana. Although the title suggests a triptych (Marooned in no-man's-land, Nothing to do and Essence of me), the work more closely resembles a mosaic of short stories bursting with vivid images of exhilaration, depravity, desire and isolation. Narrator Pedro Juan, middle-aged and fed up, has rejected his career as a journalist because "I always had to write as if stupid people were reading me." Resisting the mass exodus from Cuba of August 1994, Pedro Juan now wanders the streets of Havana like a footloose Bacchus, indulging himself with women, marijuana and rum. He survives through a series of menial jobs. His rooftop apartment in central Havana has a spectacular Caribbean view but is, like all dwellings in the decaying economy, frequently without water. Pedro Juan is imprisoned more than once for minor crimes; after one lengthy sentence, he returns home to discover that his lover has replaced him with another man. He eventually drifts back into the urban maelstrom. Prolific, explicit sex scenes reinforce the plight of the artist, and thus a society, limited to physical pleasures where life offers no intellectual or creative rewards. "It's been years since I expected anything, anything at all, of women, or of friends, or even of myself, of anyone." Gutiérrez's talent lies in creating a macho, self-abusive protagonist who remains engagingly sympathetic. This searing, no-holds-barred portrait of modern Cuba, expertly translated by Wimmer into prose strong in the rhythms and vulgar beauty of the city, comes complete with a sexy jacket photo. It will attract readers who like their fiction down, dirty and literate.

5 shots from "DIRTY HAVANA TRILOGY"

NEW THINGS IN MY LIFE

EARLY that morning, there was a pink postcard sticking out of my mailbox, from Mark Pawson in London. In big letters he had written, "June 5, 1993, some bastard stole the front wheel of my bicycle." A year later, and that business was still bothering him. I thought about the little club near Mark's apartment, where every night Rodolfo would strip and do a sexy dance while I banged out weird tropical-improvisational music on bongo drums, shaking rattles, making guttural noises, trying anything else I could think of. We had fun, drank free beer, and got paid twenty-five pounds a night. Too bad it couldn't have lasted longer. But black dancers were a hot commodity, and Rodolfo left for Liverpool to teach modern dance. I was broke, and I stayed at Mark's until I got bored and came back.

Now I was training myself to take nothing seriously. A man's allowed to make lots of small mistakes, and there's nothing wrong with that. But if the mistakes are big ones and they weigh him down, his only solution is to stop taking himself seriously. It's the only way to avoid suffering—suffering, prolonged, can be fatal.

I stuck the postcard up behind the door, put on a tape of Armstrong's "Snake Rag," felt much better, and stopped thinking. I don't have to think while I'm listening to music. But jazz like this cheers me up too and makes me feel like dancing. I had a cup of tea for breakfast, took a shit, read some gay poems by Allen Ginsberg, and was amazed by "Sphincter" and "Personals ad." I hope my good old asshole holds out. But I couldn't be amazed for long, because two very young friends of mine showed up, wanting to know if I thought it would be a good idea to launch a raft from Cabo San Antonio heading for Cabo Catoche, or whether it would be better to take off north directly for Miami. Those were the days of the exodus, the summer of '94. The day before, a girlfriend had called me to say, "What'll we do now that all the men and kids are leaving? It's going to be hard." Things weren't like that, exactly. Lots of people were staying, the ones who couldn't live anywhere else.

Well, I've done a little sailing on the Gulf and I know that way's a trap. Showing them the map, I convinced them not to try for Mexico. And I went down to see their big six-person raft. It was a flimsy thing made of wood and rope lashed to three airplane tires. They were planning to take a flashlight, compass, and flares. I bought some slices of melon, went over to my ex-wife's house. We're good friends now. We get along best that way. She wasn't home. I ate some melon and left the rest. I like to leave tracks. I put the leftover slices in the fridge and got out fast. I was happy in that house for two years. It's not good for me to be there by myself.

Margarita lives nearby. We hadn't seen each other in a while. When I got there, she was washing clothes and sweating. She was glad to see me and she went to take a shower. We had been lovers on the sly—sorry, I have to call it something—for almost twenty years, and when we get together, first we fuck and then we have a nice relaxed conversation. So I wouldn't let her shower. I stripped her and ran my tongue all over her. She did the same: she stripped me and ran her tongue all over me. I was covered in sweat, too, from all the biking and the sun. She was getting healthier, putting weight back on. She wasn't all skin and bones the way she used to be. Her buttocks were firm, round, and solid again, even though she was forty-six. Black women are like that. All fiber and muscle, hardly any fat, clean skin, no zits. I couldn't resist the temptation, and after playing with her for a little while, after she had already come three times, I eased myself into her ass, very slowly, greasing myself well with cunt juice. Little by little. Pushing in and pulling out and fondling her clit with my hand. She was in agony, but she couldn't get enough. She was biting the pillow, but she pushed her ass up, begging me to get all the way in. She's fantastic, that woman. No one gets off the way she does. We were linked like that for a long time. When I pulled out, I was all smeared in shit, and it disgusted her. Not me. I have a strong sense of the absurd, and it keeps me on guard against that kind of thing. Sex isn't for the squeamish. Sex is an exchange of fluids, saliva, breath and smells, urine, semen, shit, sweat, microbes, bacteria. Or there is no sex. If it's just tenderness and ethereal spirituality, then it can never be more than a sterile parody of the real act. Nothing. We took a shower, and then we were ready to have coffee and talk. She wanted me to go with her to El Rincón. She had to keep a vow she made to San Lázaro and she asked me to go with her the next day. Really, she asked so sweetly I said I would. That's what I love about Cuban women—there must be other women like them too, in America, maybe, or Asia—they're so sweet you can never say no when they ask you for something. It's not that way with European women. European women are so cold they give you a chance to say NO at every turn, and you feel good about it too.

Later I came home. The afternoon was already cooling off. I was hungry, which was no surprise, since all I had in my stomach was tea, a slice of melon, and some coffee. At home I ate a piece of bread and washed it down with another cup of tea. I was getting used to lots of new things in my life. Getting used to poverty, to taking things in stride. I was training myself to be less ambitious, because if I didn't, I'd never make it. In the old days, I always used to need things. I was dissatisfied, wanting everything at once, struggling for more. Now I was learning how not to have everything at once, how to live on almost nothing. If it were any other way, I'd still be stuck with my tragic view of life. That's why poverty didn't bother me anymore.

Then Luisa called. She was coming for the weekend. And Luisa's a sweetheart. Too young for me, maybe, but it doesn't matter. Nothing matters. It started to rain, thunder crashed, the wind came in gusts, and the humidity was terrible. That's the way it is in the Caribbean. It'll be sunny, then all of a sudden the wind picks up and it starts to rain and you're in the middle of a hurricane. I needed some rum, but there was no way to get it. I had money, but there was nothing to buy. I lay down to sleep. I was sweaty and the sheets were dirty, but I like the smell of my own sweat and dirt. It turns me on to smell myself. And Luisa was coming any minute. I think I fell asleep. If the wind got stronger and ripped the tiles off the roof, I wouldn't care. Nothing matters.

©Pedro Juan Gutiérrez

MEMORIES OF TENDERNESS

I WAS looking for something good on the radio, and I stopped at a station playing Latin music, salsa, son, that kind of thing. The music ended, and the laid-back guy with the rough voice started to talk, the one who'll go on about anything, his kids, his bike, what he did last night. His voice is the kind that gets under your skin, and he talks tough and slangy, like he's never been anywhere but Central Havana, the kind of brother who'll come up and say, "Hey, man, what you need? I got a deal for you."

My wife and I listened to him, and we really liked it. Nobody on the radio was doing what he was doing. He'd play good Latin music, say something, pause for a minute, put on another record, and then it was on to the next thing. No long explanations or showing off. He seemed smart, and I'm always happy to come across smart, proud black guys, instead of the kind who won't look you in the eye and who have that pathetic cringing slave mentality.

Well, we'd always listen to him at home, back when we were happy and life was good, no matter that I was earning an unhealthy and cowardly living as a journalist, always making concessions, everything censored, and it was killing me because each day I felt more like I was prostituting myself, collecting my daily ration of kicks in the ass.

Then she went back to New York, wanting to be seen and heard. Just like everybody else. Nobody wants to be condemned to darkness and silence. They all want to be seen and heard, want a turn in the spotlight. And if possible, they'd like to be bought, hired, seduced. Did I write "everybody wants"? That's not quite right. It should have been: "We all want to be seen and heard."

She's a sculptor and a painter. In the art world, that makes her "popular." And that's supposed to be a good thing. It's comforting to be popular. Anyway, she left again. And I was kicked out of journalism because each day I was more reckless, and reckless types weren't wanted. Well, it's a long story, but in the end what they told me was: "We need careful, reasonable people, people with good sense. We don't want anybody reckless, because the country's going through a very sensitive and important phase in its history."

Around the same time, I found out that the guy with the rough, boozy voice wasn't black. He was white, young, a college student, well-educated. But his persona suited him.

So I was very lonely. That's what always happens when you love holding nothing back, like a kid. Your love goes off to New York for a long time—goes to hell, you might say—and you're left lonelier and more lost than a shipwreck in the middle of the Gulf Stream. The difference is that a kid recovers quickly, whereas a forty-four-year-old guy like me keeps kicking himself, and thinks, "Not again" —and wonders how he could be such an idiot.

The fact that it was Jacqueline made it even worse, because she holds an important record in my manly existence: she once had twelve orgasms with me, one after the other. She could have had more, but I couldn't hold out, and I went and had mine. If I had waited for her, she might have gotten close to twenty. Other times she had eight or ten. She never broke her record. Because we were happy, we got a lot of joy out of sex. The thing with the twelve orgasms wasn't a competition. It was a game. A great sport for keeping young and fit. I always say, "Don't compete. Play."

Well, in any case, Jacqueline was too sophisticated for 1994 Havana. She was born in Manhattan, descended from a mix of three generations of English, Italians, Spaniards, French, and Cubans originally from Santiago de Cuba who scattered toward New Orleans and all over the Caribbean, as far away as Venezuela and Colombia. A crazy family. Her father had been in Normandy, was a D-day veteran. Anyway, she's a complicated woman, and too much work for a simple tropical male like me. She would say, "Oh, there's nobody sophisticated left in Havana. People just keep getting tackier, shabbier, more countrified." Something wasn't right about that. Either it was Jacqueline's elegance, or everybody else's tackiness, or my stupidity, because as far as I could tell, everything was fine and I was happy, even if the poverty got worse every time you turned around.

When I was left alone, I had lots of time to think. I lived in the best possible place in the world: an apartment on the roof of an old eight-story building in Central Havana. In the evening, I'd pour myself a glass of very strong rum on the rocks, and I'd write hard-boiled poems (sometimes part hard-boiled, part melancholy), which I'd leave scattered all over the place. Or I'd write letters. At that time of day, everything turns golden, and I'd survey my surroundings. To the north, the blue Caribbean, always shifting, the water a mix of gold and sky. To the south and east, the old city, eaten away by the passage of time, the salt air and wind, and neglect. To the west, the new city, tall buildings. Each place with its own people, their own sounds, their own music. I liked to drink my rum in the golden dusk and look out the windows or sit for a long time on the terrace, watching the mouth of the port and the old medieval castles of naked stone, which in the smooth light of afternoon seem even more beautiful and eternal. It all got me thinking with a certain clarity. I'd ask myself why life was the way it was for me, and try to come to some kind of understanding. I like to step back, observe Pedro Juan from afar.

It was those evenings of rum and golden light and hard-boiled or melancholy poems and letters to distant friends that helped make me sure of myself. If you have ideas of your own—even only a few—you have to realize that you'll always be coming up against detractors, people who'll stand in your way, cut you down to size, "help you understand" that what you're saying is nothing, or that you should avoid a certain person because he's crazy, a fag, a traitor, a loser; somebody else might be a pervert and a voyeur; somebody else a thief; somebody else a santero, spiritist, druggie; somebody else trash, shameless, a slut, a dyke, rude. Those people reduce the world to a few hybrid types, colorless, boring, and "perfect." And they want to turn you into a snob and a prick too. They swallow you up in their private society, a society for ignoring and supressing everyone else. And they tell you, "That's life, my friend, a process of natural selection. The truth is ours, and everybody else can go fuck themselves." And if they spend thirty-five years hammering that into your skull, later, when you're on your own, you think you're better than everybody else and you're impoverished and you miss out on the joy of variety, when variety is the spice of life, the acceptance that we're not all alike and that if we were, life would be very dull.

Well, then the guy with the rough, boozy voice turned up on the radio again, fooling around a little, and slotted in a Puerto Rican salsa orchestra, and I danced for a while. Until I asked myself, "What the hell am I doing here dancing all alone?" Then I turned the radio off and went out. "I'm going to Mantilla," I thought. I roamed around until I caught one bus and then another, and I got to Mantilla, which is on the outskirts of the city, and which I like because out there you can see red earth and the green of the land and herds of cattle. I have some friends in the neighborhood—I used to live there, years ago. I went to see Joseíto, a taxi driver who lost his job in the crisis and now was gambling for a living. He'd been supporting himself gambling for two years. In Mantilla, there were lots of illegal little gambling clubs. The police made a sweep sometimes and wiped out two or three, locked everybody up for a few days, and then let them go. I had three hundred pesos in my pocket, and Joseíto convinced me to play. He was carrying ten thousand himself. He was in it for the big money. We went to one of his lucky houses. And he was lucky. I lost all my money in fifteen minutes. I don't know why the hell I let Joseíto drag me along. I never win anything when I gamble, but he was raking it in from the start. By the time I left, he had already pocketed five thousand pesos. Lucky bastard. With his kind of luck, I'd be riding high. Well, he has a good life in Mantilla, and he always says, "Oh, Pedro Juan, if I'd had any idea, I would've gotten rid of that fucking taxi a long time ago."

I was pissed about the money. It bothers me to lose. I get irritated every time, and it bothered me that Joseíto could make a living so easily, whereas whenever I play a hand of cards or pick up some dice I start losing right away. I'm not a jinx, because I give everybody else good luck. It happens all the time. Once I bought an old, beat-up car and I left it parked out in front of the building for a week, just sitting there; it had two or three things wrong with it, and fixing it was going to be expensive. Well, a few days later, an old Spaniard came up to me to tell me that everybody in the neighborhood was playing the car's license plate number—03657—in the lottery. Laughing, the old man said, "We're going to have to pay you a commission, Pedro Juan. Last night the butcher won three thousand pesos on 57. What do you think about that?"

"What do I think? I think the son of a bitch should at least pay for my repairs. The car's been sitting there for a week because I'm so broke."

"Damn! Everybody making money on your car, and you making shit."

That's right. I'm hopeless at gambling, and at a whole lot of other things too.

When I left the little club where José was getting rich, I had a few coins in my pocket. Enough to take the bus back to downtown Havana. But I needed a shot of rum. Losing had really pissed me off, and I was feeling aggressive. A little rum calms me down. "I'll go see Rene," I said to myself. Rene (I just call him Rene because he's a good friend) is a fine press photographer. We used to work together a lot, years ago. But then he was caught taking nude photos. They were simple photos of naked girls. No fucking, no black dick sucking, nothing like that. Just nude studies of beautiful girls. There was a scandal. He was kicked out of the Party, ejected from the profession, and expelled from the Association of Journalists. The last straw was when his wife kicked him out of the house and told him she had become "disenchanted" with him. Well, that's how it was. Cuba at the height of its existence as socialist construct maintained a virginal purity, in exquisite Inquisitorial style. And all of a sudden, the guy realized that his life was over. He was living in a dump in Mantilla with a fucked-up son who supported himself by selling grass, but who spent more time in jail than he spent in their dump selling the stuff he brought back from Baracoa. He sold coconut oil, coffee, and chocolate too, on the black market, but he made his real money dealing in excellent mountain weed and he brought so much back that he could sell it cheap.

Rene was alone now. His druggie son had left by raft for Miami in the exodus of August 1994. And he had no idea what had happened to him.

"I don't know where he is, whether he got to Miami, or whether he was taken to the naval base at Guantánamo. Or whether he's in Panama. I have no idea. To hell with it, Pedro Juan. To hell with everybody. When he was here, he spent all his time telling me that if it wasn't for him, I'd be out on the street. Everybody can go fuck themselves! I've gotten the shit kicked out of me so many times I'm sick of them all."

He started to cry. He was sobbing. I thought he was probably stoned.

"Come on, Rene, I'm your friend. Cut it out, man. Let's go get some rum."

"There's a little left in the kitchen. Bring it here."

It was rat poison. Half a bottle of cockroach repellent. I swallowed down a shot.

"Rene, for God's sake, you're killing yourself with this aguardiente. What the fuck is it made of?"

"Sugar, believe it or not. My next door neighbor makes it. I know it's shit, but I'm used to it now. It doesn't seem so bad to me. Fancy a joint? There are some papers in the drawer."

"Why are you talking like that? Since when are you the big Spaniard?"

"I picked it up from the whores who come here. They're so dumb they talk to me like the Spaniards who hang out with them. They're always saying `have a light?' `good chap,' `let's have a word.' They're crazy. So am I. I'm crazy and I talk just like those Spaniards and their black bitches."

We lit the joints and we sat in silence. I shut my eyes to savor mine. That Baracoa weed has a smell and taste like nothing else. But it's strong. I didn't inhale much. I was thinking I should go to Baracoa and bring back a kilo or two. Rene's son would bring back coconut oil, coffee, and chocolate too because the smell of the coffee masked the smell of the weed. I could do the same thing. And I'd make a few pesos. That's what I was thinking when I felt Rene get up, pull a photo album out of a drawer, and hand it to me.

"Look at this, Pedro Juan."

He was already stumbling over his words, after all the aguardiente and the grass. He dropped into his armchair again, flattened and hopeless. I had to get the hell out of there. The air in that place reeked of shit and despair. And it's contagious. It's like breathing in a poisonous gas that gets in your blood and suffocates you. I couldn't keep talking to Rene. I needed a buddy who was tough. The kind of guy who could get me out of my slump and away from all my memories of happiness. I needed to make myself hard like a rock.

I opened the album. It was a collection of nudes. There were at least three hundred of them, in every position. Blacks, mulattas, whites, brunettes, blondes. Smiling ones and serious ones. Some were in pairs, kissing or embracing or feeling each other's tits.

"So what is this, Rene?"

"Whores, man. A catalog of whores. Lots of taxi drivers keep photos like this for the tourists. They advertise the product around town, the tourist picks what he wants, and they take him to the right place."

"Then you're shooting pictures of stars! Rene, photographer to the stars!"

"Rene, photographer to the whores! I'm finished, man. I'm washed up."

"Don't talk shit, Rene. If you're making good money that way ..."

"You know I'm an artist. This is crap, kid."

"Listen, you're driving me crazy. Don't be such an asshole. Take advantage of these whores. If I were you, I'd take the damn photos for the catalogs, and then I'd take good nude shots, powerful ones of whores in their beds, in their rooms, in their world, in black and white, and then in a few years I'd put together an incredible exhibition: `Whores of Havana.' And you'd be launched with the kind of show even Sebastião Salgado couldn't put together."

"In this country? The whores of Havana?"

"In this country or wherever. Work and then find a place to show your work. Then if they shut you down here, go somewhere else, anywhere. But whatever you do, get off your ass and out of this fucking room."

"Well ... it's not a bad idea."

"Of course it's not. Try it, and I promise you'll get back on track. Listen, did your son have partners in Baracoa?"

"What do you want to do?"

"Bring back a little weed. I'm cleaned out, Rene. I have to make a few pesos."

"If you go, look up Ramoncito El Loco. He lives on the way out of Baracoa, near La Farola. Everybody knows who he is. Tell him you're my partner, and that this is for me. That way he'll give you a deal. But don't hang out with him, because everybody knows the old man's always been a dealer. You'll get busted."

"All right, brother. Take care of yourself. We'll be in touch."

I had to hurry to Baracoa. After I took care of business, maybe I could find myself one of those big-assed Indian women who make you feel like you've got the sweetest dick in the world. The Indians there have barely mixed with whites or blacks. A little trip would be worth the trouble. The people there are different.

©Pedro Juan Gutiérrez

BURIED IN SHIT

IN THOSE days, I was pursued by nostalgia. I always had been, and I didn't know how to free myself so I could live in peace.

I still haven't learned. And I suspect I never will. But at least I do know something worthwhile now: it's impossible to free myself from nostalgia because it's impossible to be freed from

memory. It's impossible to be freed from what you have loved.

All of that will always be a part of you. The yearning to relive the good will always be just as strong as the yearning to forget and destroy memories of the bad, erase the evil you've done,

obliterate the memory of people who've harmed you, eliminate your disappointments and your times of unhappiness.

It's entirely human, then, to be engulfed in nostalgia and the only solution is to learn to live with it. Maybe, if we're lucky, nostalgia can be transformed from something sad and depressing

into a little spark that sends us on to something new, into the arms of a new lover, a new city, a new era, which, no matter whether it's better or worse, will be different. And that's all we ask

each day: not to squander our lives in loneliness, to find someone, to lose ourselves a little, to escape routine, to enjoy our piece of the party.

That's where I was, still. Coming to all those conclusions. Madness lurked, and I eluded its grasp. Too much had happened in too short a time for one person to handle, and I left Havana for a few

months. I lived in another city, making some deals, selling a used refrigerator and a few other things, staying with a crazy girl - crazy in the purest sense, unspoiled - who had been in prison

many times and was covered in tattoos. The one I liked best was the one she had on the inside of her left thigh. It was an arrow pointing to her sex and lettering that read simply: EAT AND ENJOY.

One buttock read: PROPERTY OF FELIPE, and the other: NANCY I LOVE YOU. JESUS was inscribed in big letters on her left arm. And on her knuckles there were hearts enclosing the initials of some of

her lovers.

Olga was barely twenty-three, but she had led a wild life: lots of grass, drinking, and every kind of sex. She had syphilis once, but she got over it. My stay with her lasted a month; it was fun.

Living in Olga's squalid room was like living in the middle of an X-rated film. And I learned. I learned so much in that month that maybe someday I'll write a Guide to Perversion. I went back to

Havana with enough money not to have to work for a good long time, but when I got to Miriam's, she was terrified, "Get away from here! He knows everything and he's going to kill you!" She was

bruised all over and she had a cut above her left eyebrow. Her husband was released after three years in prison. He didn't serve out his ten-year sentence. And as soon as he got to the building,

his friends told him about Miriam and me. He practically beat her to death. Then he found a butcher's knife and swore not to rest until he had slit my throat.

The man was dangerous, so I thought I had better steer clear of Colón until he calmed down. But I had nowhere to go. I went to Ana María's place. I told her my story, and she let me sleep there,

on her floor, for a few nights, but the truth was, I was disrupting her romance with Beatriz. I could hear them making love in the dark, Beatriz playing the man's role, and all of that really

turned me on. I jerked off until one night I couldn't stand it anymore, and then I went over to their bed with my dick erect and superhard, turned on the light, and said, "Up and at 'em! Let's

all three of us get it on now!"

Beatriz was prepared for my attack. She stuck her hand under the bed and pulled out a thick length of electrical cord, the kind with a lead lining, and she threw herself at me like a wild animal.

"This is my girlfriend, you faggot, go fuck yourself in your mother's cunt!" I didn't know a woman could be so strong. She hit me savagely. She battered my lips and teeth, she split my nose, and

she beat me to the ground, where I lay stunned by the blows of the cable raining on my head. Half-unconscious, I could hear Ana María shouting, begging her to leave me alone. Then they tossed a

little cold water in my face and dragged me out into the corridor of the building. They dumped me there and closed the door. Beatriz kept repeating, "Bastard, ungrateful son of a bitch. You can't

trust any one, Ana María, anyone."

I was sprawled there for a long time. I didn't have the strength to get up, and my ribs and back hurt. At last I made an effort and managed to get to my feet. If Beatriz happened to come to the

door and see I was still there, she would lay into me again, mercilessly. She was stronger and tougher than a trucker. I walked for a while around Industria, and I stretched out on a bench in

Parque La Fraternidad. People thought I was a drunk, and they went through my pockets, looking for something to steal. Every half hour, someone patted me down, but I had hidden my money in a book

at Ana Maria's place.

When morning came, I went to the emergency hospital. They fixed me up a little. I didn't have a penny, and it was too soon to try to get my money from Ana María's place. It seemed best to wait a

few days.

By now I was battered, dirty, in need of a shave, and desperate enough to beg. I went to the church of La Caridad, in Salud y Campanano, sat on the steps by the door looking hungry and for~rn,

and stretched out my hand. Little good it did me. All the money was going to an old woman who was there already. She had a picture of San Lázaro and a small cardboard box printed with the message

that she was fulfilling a vow. When the church was locked that night, I had just a few coins and I was desperately hungry. It had been more than twenty four hours since I had anything to

eat.

I begged at a few houses for food but starvation was fierce everywhere. Everybody was hungry in Havana in 1994. An old black woman gave me a few pieces of cassava and when she looked me in the

eye, she said, "What are you doing like this? You're a son of Changó."

"And of Ochún too.

"Yes, but Changó is your father and Ochún your mother. Pray to them, son, and ask for help. They won't let you down."

"Thank you, mother."

That was how I spent the next few days, until my aches and pains were gone. Then I picked up an iron rod in the street, hid it in my pants, under my shirt, and headed for Ana María's place. It

was mid-morning, and I calculated that Beatriz would be at work.

I knocked, and Ana María opened the door. She tried to shut it again in my face, but I blocked it with my iron rod. Pushing my way in, I swept her to one side, and she screamed and went running

to get a knife out of the sink.

"Ana María, calm down. I'm not going to do anything. I'm going to pick up something I left here, and then I'll go."

"You didn't leave anything here. Get out! Get out! All men are the same, bullies! If Beatriz were here, she'd smash your head in, you bastard. Get out!"

By then I had the book in my hand, I opened it, and there was my money, shining up at me. I put it in my pocket and left. She quieted down all of a sudden, and I tried to disappear as fast as I

could. If she thought to scream for someone to stop me, saying I had robbed her, then I'd be screwed.

The first thing I did was buy a bottle of rum. It had been a long time since I'd had a drink. I went to an acquaintance's house and bought it from him. It was black-market rum, expensive but

good. I opened the bottle, and we had a few drinks. He asked me why I was so fucked up, and I told him part of the story. Not much of it.

"Why don't you find yourself some old guy to take care of? Around the corner there's a sick old man who lives alone. He's close to eighty years old and he's a bastard, but if you're patient, you

could make him behave. His wife died a few months ago, and he's about to die himself of starvation and filth. Get yourself in his good graces, move in with him, take care of him, clean him up,

bring him a little food, and when he dies, you can have the house. You'd be better off there than on the street."

We finished the bottle. I bought another one, and I went to see the old man. He was a tough old guy. A very old black man. Ravaged but not completely destroyed. He lived at 558 San Lázaro, and he

spent every day sitting silently in his wheelchair in the doorway, watching the traffic, breathing in gasoline fumes, and selling boxes of cigarettes slightly cheaper than in the stores. I bought

a pack from him, opened it, and offered it to him, but he refused. I offered him rum, but he wouldn't take that either. I was in a good mood. Now that I had a little money in my pocket, a bottle

of rum, and a pack of cigarettes, I was beginning to see the world in a new light. I told the old man that, and we talked for a while. I had half a bottle of rum in me, and that made me chatty

and entertaining. An hour and a few drinks later (finally he agreed to have a drink with me), the old man gave me an in: he used to work in the theater.

"Where? At the Martí?"

"No. At the Shanghai."

"Ah. And what did you do there? I've heard it was a strip joint. Is it true that they shut it down as soon as the Revolution began?"

"Yes, bqt I hadn't been working there long. I was Superman. There was always a poster just for me: 'The one and only Superman, exclusive engagement at this theater.' Do you know how long my prick

was when it was fully erect? Twelve inches. I was a freak. That's how they advertised me: 'A freak of nature . . . Superman...twelve inches - thirty centimetres - one foot of Superprick . . .

appearing now. . . Superman!'"

"Was it just you on stage?"

"Yes, just me. I would come out wrapped in a red and blue velvet cape. In the middle of the stage, I'd stop in front of the audience, fling open the cape, and there I'd be, naked, with my prick

limp. I would sit in a chair, and it would seem I was looking at the audience. What I was really looking at was a white girl with blond hair who was sitting in the wings, on a bed. That woman

made me crazy. She would masturbate and when she was hot, a white man would join her and she'd do everything. Everything. It was amazing. But no one saw them. It was just for me. Watching that,

my prick would swell to the bursting point, and without ever touching it, I would come. I was in my early twenties, and I shot out such powerful jets of come that they reached the first row of

the audience and showered all those bastards."

"And you did that every night?"

"Every night. Without missing a one. I made good money, and when I came in those long spurts and groaned with my mouth open, my eyes rolled back in my head, and got up out of the chair dazed like

I was stoned, the bastards fought over the right to frolic in the showers of my sperm like carnival streamers, and then they would toss money onto the stage and stamp their feet and shout,

'Bravo, bravo, Superman!' They were my fans and I was their favorite performer. On Saturdays and Sundays, I earned more because the theater filled up. I became so famous that tourists from all

over the world came to see me."

"And why did you give it up?"

"Because that's life. Sometimes you're up and sometimes you're down. By the time I was thirty-two or so, the jets of come weren't as strong and then there were times when I lost concentration and

sometimes my prick would droop a little and straighten up again. Lots of nights, I couldn't come at all. By then I was half-crazy, because I had spent so many years straining my brain. I took

Spanish fly, ginseng; in the Chinese pharmacy on Zanja, they made me a tonic that helped, but it made me jittery. No one could understand the toll my career was taking on me. I had a wife. We

were together for our whole lives, more or less, from the time I came to Havana until she died a few months ago. Well, during all of that time, I was never able to come with her. We never had

children. My wife didn't see my jism in twelve years. She was a saint. She knew that if we fucked as God willed and I came, then at night I wouldn't be able to do my number at the Shanghai. I had

to save up my jism for twenty-four hours to do the Superman show."

"Incredible self-control."

"It was either control myself or die of hunger. It wasn't easy to make money in those days."

"It's still hard."

"Yes. The poor are born to be shit on."

"And what happened then?"

"Nothing. I stayed at the theater for a while longer, doing filler; I put together a little skit with the blond girl, and people liked it. They advertised us as 'Superprick and the Golden Blonde,

the horniest couple in the world.' But it wasn't the same. I earned very little. Then I joined a circus. I was a clown, I took care of the lions, I was a base-man for the balancing acts. A little

bit of everything. My wife was a seamstress, and she cooked. For years, that's what we did. In the end, life is crazy. It takes many unexpected turns."

We had another drink from the bottle. He let me stay there that night, and the next day I got him some porn magazines. Superman was a professional Peeping Tom. The only guy in the world who had

made a living watching other people fuck. We had really hit it off, and I thought I'd give him a thrill with those magazines. He leafed through them.

"These have been outlawed for thirty-five years. In this country a person is practically forbidden to laugh. I used to like these. And my wife did too. We liked to jerk off together looking at

the white girls."

"Was she black?"

"Yes, but she was very refined. She knew how to sew and embroider, and she worked as a cook for some rich people. She wasn't just any old black girl. But she followed my lead. In bed she was as

crazy as I was."

"And don't you like these magazines anymore, Superman? Keep them, they're a gift."

"No, son, no. What good will they do me now? Look."

He lifted up the small blanket that covered his stumps. He no longer had prick or balls. Everything had been amputated along with his lower limbs. It was all chopped off, all the way up to his

hip bones. There was nothing left. A little rubber hose came out of the spot where his prick used to be and let fall a steady drip of urine into a plastic bag he carried tied at his waist.

"What happened to you?"

"High blood sugar. The gangrene crept up my legs. And little by little, they were amputated. They even took my balls. Now I really don't have any balls! Ha ha ha. I used to be ballsy. The

Superman of the Shanghai! Now I'm fucked, but no one can take away what I've had."

And he laughed heartily. Not even a hint of irony. I got along well with that tough old man, who knew how to laugh at himself. That's what I'd like: to learn to laugh at myself. Always, even if

they cut off my balls.

©Pedro Juan Gutiérrez

STARS AND LOSERS

I LIKE to smell my armpits while I masturbate. The smell of sweat turns me on. It's dependable, sweet-smelling sex. Especially when I'm horny at night and Luisa is out making money. Though it's

not the same anymore. Now that I'm forty-five, my libido isn't what it used to be. I have less semen. Barely one little spurt a day. I'm getting old: slackening of desire, less semen, slower

glands. Still, women keep fluttering around me. I guess I've got more soul now. Ha, a more soulful me. I won't say I'm closer to God. That's a silly thing to say, pedantic: "Oh, I'm closer to

God." No. Not at all. He gives me a nod every once in a while. And I keep trying. That's all.

Well, it was time to get out. Solo masturbation is the same as solo dancing: at first you like it and it works, but then you realize you're an idiot. What was I doing standing there naked jerking

off in front of a mirror? I got dressed and went out. I had put on dirty, sweaty clothes. Today I was definitely repulsive. Going down the stairs, I ran into the morons crying on the fifth floor.

They're young, but they're morons, mongoloids, or crazy, loony, I don't know, some kind of retards, idiots. They've been together for years. They stink of filth. They shit in hidden places on the

stairs. They pee every-where. Sometimes they walk around their room naked and come right up to the door. They make a racket, they slobber. Now she was sitting on a stair step wailing at the top

of her lungs. "I love you so much, but I can't. I love you so much, but I can't do it that way. I love you so much. Oh, darling! Ohhhh! I love you so much."

He lit a cigarette, moved to one side to let me by, and said, "I know you love me, sweetie, I know you love me, sweetie." And he started sobbing too.

At least today they hadn't crapped on the stairs. What they needed was a good grooming with a stiff brush, soap, and a cold shower. Coming out into the four o'clock light, I stopped: what to do?

Should I go to the gym and box a little, or head for Paseo and Twenty-third? Last time I won twenty dollars at Russian roulette. It was the right time of day. Someone would surely be there. I

went off to play Russian roulette.

I like to walk slowly, but I can't. I always walk fast. And it's silly. If I don't know where I'm going, what's the hurry? Well, that's probably exactly it: I'm so terrified, I can't stop

running. I'm afraid to stop for even a second and find out I don't know where the fuck I am.

I stopped in at Las Vegas. Las Vegas is immortal. It will always be there, the place where she sang boleros, the piano in the dark, the bottles of rum, the ice. All of it just as it always has

been. It's good to know some things don't change. I gulped down two shots of rum. It was very quiet and very cold and very dark. So much heat and humidity and light outside, and so much noise.

And all of a sudden, everything is different when you come into the cabaret. It's really a tomb, where time has stopped forever. Just sitting there for a minute, it made me think.

Soul and flesh. That was it. One glass of rum and already the two were in painful confrontation, the soul on one side, flesh on the other. And me torn in between, chopped into bits. I was trying

to understand. But it was difficult. Almost impossible to comprehend anything at all. And the fear. Ever since I was a child, there was always the fear. Now I had given myself the task of

conquering it. I was going to a gym to box and I was toughening up. I'd box anyone, though I was always trembling inside. I tried to hit hard. I tried to let myself be swept away, but it was

impossible. The fear was always there, going about its own business. And I'd say to myself, "Oh, don't worry, everybody's afraid. Fear springs up before anything else. You've just got to forget

it. Forget your fear. Pretend it doesn't exist, and live your life."

I downed two more shots of rum. Delicious. I was in a delicious state, I mean. The rum wasn't so delicious. It tasted like diesel fuel. And I went off to play Russian roulette. I had seven

dollars and twenty-two pesos left. Not bad. Things had been much worse and I had always managed to stay afloat.

There were people at Paseo and Twenty-third. And Formula One was there, with his bicycle. It was the right time of day. Almost five o'clock. There's lots of traffic at that intersection. Traffic

in all directions. We settled our bets. I played my seven dollars at five to one. If I won, I'd have thirty-five. I always bet that the kid will make it across. A black man, wearing silver and

gold chains every-where, even on his ankles, went by. That asshole always bets he won't make it. "I bet on blood, man. Always blood. That's all you need to know." Whenever we ran into each other

he'd take my bet at five to one. Even so,I never made much money.

A month ago, I set a record: I won thirty-five dollars in one shot. I was lucky. Delfina was with me. I cashed in, showed her the money, and she went crazy. I call her Delfi because she has the

most half-assed name in Havana. We went to the beach, and we rented a room there and partied for two days, with all the food, rum, and marijuana we wanted. Delfi is a beautiful, sexy black woman,

but I found out I couldn't handle orgies like that anymore. All Delfi wanted was prick, rum, and marijuana. In that order. But I couldn't always be fucking. When I couldn't get it up, insatiable

Delfi tried to see what she could do by sticking her finger up my ass. I slapped her a few times and said, "Get your finger out of my ass, you black bitch." But still, we kept fucking and

fucking. Maybe out of inertia. When the rum and the marijuana and the dollars ran out, I came back to my senses. I ached everywhere: my head, my ass, my throat, my prick, my pockets, my liver, my

stomach. Not Delfi. She was twenty-eight years old, and she was a black powerhouse, muscular and tough. She was ready to keep going for two or three more days without stopping. Tireless, that

woman. Amazing. She's a marvel of nature.

The kid who was going to play Russian roulette picked up his bicycle. He had a red handkerchief tied around his head. He was just a kid, mulatto, fifteen or sixteen years old, and never separated

from his bicycle. He wouldn't even let go of it to take a shit. It was a small, sturdy bike, shiny chrome with fat tires. He earned his living from it, He got twenty dollars straight up each time

he made it across. He was good. Other times, he performed stunts, and he charged for them, too: he'd make ten children lie down in a row in the middle of the street, then he'd back up several

feet, cross himself, take off like a shot, and sail over the kids. He'd do that on any street, wherever he was called. People bet on him, but he wouldn't bet. He'd take his twenty dollars and get

out. He was vain, and he'd say to people, "Formula One, that's me."

Now Formula One was riding up Paseo. He did a few jumps on his bicycle between cars. He looped, leapt into the air, twirled a few times, and landed on one wheel. He was a master. People watched

him, but they didn't know what the kid was up to. There were seven of us, and we played it cool on the corner by the convent under the trees. There wasn't even one policeman around. Formula had

to wait for an order from one of us. Just as the light turned green on Twenty-third, a guy next to me dropped his arm and Formula took off like lightning down Paseo. On Twenty-third, heading

toward La Rampa, thirty cars accelerated when the light turned green, rush hour traffic raring to go. And heading in the opposite direction, up the street toward Almendares, came thirty or forty

more, growling and desperate. In total, Formula had seventy chances to be crushed to death and just one to live. My seven dollars were in the balance. If the kid was killed, I'd have nothing. I

needed Formula to cross safely and earn his twenty dollars. And he made it! He was a flash of light. I don't know how the fuck he did it. Just like a bird. All of a sudden, he was sparkling on

the other side of Paseo, twisting in the air and laughing.

He came toward us laughing as hard as he could. "I'm Formula One!" I collected my thirty-five dollars. I gave five to Formula and called him aside. I shook his hands. They were dry and

steady.

I looked him in the eye and asked him, "Don't you get scared?"

He shrugged his shoulders. "Oh, whitey, don't make me laugh. I'm Formula One, man! Formula One!"

Before his time, four boys were killed in the same spot. I don't want to think about it. Two others didn't have the guts to go for it. That's life. Only a very few survive: the biggest stars and

the biggest losers.

©Pedro Juan Gutiérrez

CLAUSTROPHOBIC ME

FOR YEARS I’ve been trying to get out from under all the shit that’s been dumped on me. And it hasn’t been easy. If you follow the rules for the first 40 years of your life, believing everything

you’re told, after that it’s almost impossible to learn to say “no,” “go to hell,” or “leave me alone.”

But I always manage... well, I almost always manage to get what I want. As long as it isn’t a million dollars, or a Mercedes. Though who knows. If I wanted either of those things, I could find a

way to have them. In fact, wanting a thing is all that really matters. When you want something badly enough, you’re already halfway there. It’s like that story about the Zen archer who shoots his

arrow without looking at the target, relying on reverse logic.

Well, when I started to forget about important things–everyone else’s important things–and think and act a little more for myself, I moved into a difficult phase. And it was like that for years:

I was on the margins of everything. In the middle of a balancing act. Always on the edge of a precipice. I was moving on to the next stage of the adventure we call life. At the age of 40, there’s

still time to abandon routines, fruitless and boring worries, and find another way to live. It’s just that hardly anybody dares. It’s safer to stick to your rut until the bitter end. I was

getting tougher. I had three choices: I could either toughen up, go crazy, or commit suicide. So it was easy to decide: I had to be tough.

But back then I still didn’t really know how to get all the shit off my back. I just kept moving, strolling around my little island, meeting people, falling in love, and fucking. I fucked a lot:

sex helped me escape from myself. I was in my claustrophobic phase. Even in an ever-so-slightly cramped space, I’d immediately feel I was suffocating and I’d take off, howling like a wolf. It all

started when I was trapped in the elevator in my building. It’s an old machine, manufactured in the thirties, which means that it has a grate, and it’s open on the sides. It’s American, and ugly,

not like those beautiful old European elevators that still run smoothly in the hotels on the boulevard de la Villette and those other old Parisian neighborhoods. No. This elevator is a cruder,

simpler piece of junk. Very dark, because the neighbors steal the lightbulbs, with a permanent stink of urine, filth, and the daily vomit of a drunk who lives on the fourth floor. You go up or

down slowly, watching the scenery: cement, a slice of stairway, darkness, another slice of stairway, the doors to each floor, someone waiting who finally decides to take the stairs, because the

elevator stops whenever and wherever it wants. Often it decides to stop without lining up with any of the exit doors. There in front of you is the rough cement wall of the shaft, and you can hear

the people scream, “Get me out of here, goddamnit, I’m stuck!”

Like an old person with hardening of the arteries, the elevator is forgetful, and it moves up and down very slowly, shivering and snorting, as if it no longer has the strength for so much work.

And so, at one of those unexpected stops between two floors, I stuck my hand out between the door grate and the wall of the shaft, knelt down, and felt for the edge of the door on the floor below

to line the elevator up properly. That was the only way to get the machinery working again to keep moving up. And I did it: I closed the door tightly, the elevator started again, but there was no

time to get my arm out of the way. It was jammed between the wall and the grate, in a three-centimeter gap (in order to write this, I’ve just measured it). It was horrific: my arm and hand

scraping along, at the elevator’s leisurely pace, all the way to the seventh floor. I was screaming bloody murder, doubled over in pain, and I was sure my arm and my right hand were a mash of

bones and blood and shredded skin. But no. No broken bones. It was a burn, my whole arm and hand raw flesh, bleeding, the nerves scraped into a festering puree of dirt and dog shit. So from that

moment on: straight into the pit of hell. Rampant claustrophobia. When I got out of the elevator–or when I was gotten out–I stayed trapped inside myself. And I was trapped for years, trapped

inside myself. Collapsing inside.

The claustrophobia was so awful that sometimes at night I would wake with a start and jump out of bed. I felt trapped by the night, by the room, by my own self, on the bed. I couldn’t breathe.

I’d have to pee and get a drink of water and go out on the roof and watch the dark immensity of the sea, and breathe the salt air. Then I’d calm down a little.

Oh, it wasn’t really just the broken-down elevator. The elevator was the last straw. But lots of other things happened before that, which I’ll tell little by little. Later. Not now. I’ll tell

them the way a person talks to a dead man through a santera, and dedicates flowers and glasses of water and prayers to him, so that he’ll rest in peace and not fuck with those of us left on the

other side.

Well then, that’s where I was, in a state of claustrophobia, overwhelmed. Squashed like a bug. And I walked a lot, all over the place, anywhere. I was always running away. I couldn’t be at home.

Home was hell. And one day I went to a seminar for film people. If it turned out to be the right kind of thing, I could write something up for the stupid but pretentious weekly magazine I worked

for then.

The seminar, in a film school on the outskirts of Havana, lasted four days. From the very first instant, I noticed Rita Cassia: a golden-skinned Brazilian who wanted to make lots of money writing

scripts for soap operas and who had beautiful legs and was eager to get over her recent divorce. Basically, she was looking for a happy Latin lover type to cheer her up.

And that’s how it happened. All of her eroticism was concentrated in the looks she gave me. She had almond-shaped, honey-colored eyes, just like in a bolero. And when we looked at each other, it

was like kissing with lots of tongue. From that moment on, things moved fast. We ignored a famous Cuban documentary filmmaker who made great films but didn’t know how he did it. The guy was so

intuitive he had no idea where his own intuition came from. Luckily, he never tried to explain anything serious. He was a nice guy, and he told stories. We ignored him anyway, and went to walk in

a little grove of trees, making silly small talk until the electromagnetic field between us was supercharged and we kissed without exchanging a single word of love or desire. Then she told me

that during Carnival in Rio she puts on her skimpiest outfits and goes out dancing samba every night, which I guess might have something to do with her eyes and her electromagnetic field.

It was already evening and the little grove wasn’t very dense, and there were people there, because the students were very promiscuous, as you’d expect. Near us, two boys were kissing madly and

in an instant they had their zippers down and their dicks out, and they were on the ground, frantic, sucking each other in a sixty-nine. That made me even hotter, and we left. We went to the

small apartment Rita Cassia was renting, and I made her suck me before I was even out of my clothes. On the table she had a bottle of seven-year-old rum. It had been a long time since I saw those

sweet bottles of good rum. I made myself a big drink, with ice, and then another, and I was amazed: I was able to give her dick for more than an hour, everywhere, without coming. She undulated

her hips and pelvis, getting her kicks, and sprinkling me with rum. She’d take a mouthful and spray it over me and then she’d run her tongue along my skin to collect it. Sometimes rum makes me

last longer: my prick stays stiff, but I don’t come.

When I finally focused myself on coming–I was getting very tired–I managed to accumulate enough will power to pull my dick out in time to shoot all my come on her belly. And there was lots of it.

It had been two or three weeks since I had last fucked, and I had lots of jism. And Rita Cassia was carried away and she kept repeating, “Lovely, lovely, ahhh, lovely.”

From then on it was one long orgy, because after the seminar came the Festival of New Latin American Cinema, and Havana–as far as we were concerned–was paradise: lots of movies, lots of fucking,

lots of rum and good food. Cuba was just then at the beginning of the worst famine in its history. I think it was ’91. Nobody had any idea of all the hunger and crises still to come. I certainly

didn’t. All I cared about was my raging claustrophobia and the urge I had to eat. That same year, in just a few months, I had lost 40 pounds, the cause, it would seem, being lack of food.

We also amused ourselves by eluding Maria Alexandra, a successful writer of Brazilian soap opera scripts. That fine lady was a big dyke, and she besieged Rita Cassia with a splendid display of

seduction tactics: morning, noon, and night she would show up at Rita’s room with flowers, she invited her to all the cocktail parties and banquets, and she promised her incessantly that she

would help her write a good script–to sell to O’Mundo, no less.

Another of her gentlemanly tricks was to play cold war with me, alternately striking one of two poses: either she ignored me majestically, or she treated me with a fatherly yet distant

condescension. Maria Alexandra loved Rita Cassia so passionately that she demolished every obstacle in her path, any way she could. She was sure I couldn’t bestow on Rita Cassia even the tiniest

iota of the enormous pleasure, sexual and sensual, that she was capable of giving as soon as she got her hands on her. Rita Cassia, in her feminine way, stayed loyal to me, but she would turn

kittenish, charming, and witty whenever the dyke with the keys to the golden doors of O’Mundo appeared.

And that’s how the time passed. We had fun. I felt happy and ignored the fact that I was a pathetic sponger. A proud and romantic beggar. Well, as I’ve said, it was the beginning of the crisis

and our hunger was getting sharper, but a person always sees the dirt in the other man’s eye and says, “Everybody’s starving and getting thinner every day.” It’s hard to tell it like it is,

“We’re all starving, and we’re all getting thinner every day.” Rita Cassia paid for everything, because I didn’t have even a dollar in my pocket, and I calmly accepted that she would always pay.

The only other option was for me to stay home, bored, eating rice and beans and missing out on all the fun. That’s how it was, until one day it was over.

I was on the bed, with the last shot of seven-year rum in my hand. Rita Cassia was getting dressed, so we could go walking along the Malecón and say our good-byes by the sea, late at night, as

two good lovers in Havana should. It had to be a cinematic ending, under the stars, maybe even under the moon. She had already packed her suitcase. She would be leaving for the airport at three

in the morning. Then I noticed that she had left some valuable objects scattered around the room: rubber thongs, worn but still in fine shape, half a bottle of shampoo, some jars of jam,

notepads, slivers of soap, a disposable razor.

“Are you leaving all this here?”

“Sure. None of it’s any good.”

“Oh, yes it is. Those rubber thongs, the shampoo, the soap. Everything’s worth something here, even if you think it’s junk.”

“Fine then, let’s put it all in a bag and you can take it with you.”

A little while later, we were strolling along the Malecón, saying our good-byes. We’d never see each other again. She had already told me that it pained her to witness so much poverty and so much

political posturing to disguise it. She never wanted to come back. We sat for a long time, listening to the sea. She could smell it, I couldn’t. Maybe my nose was too used to it. I like to listen

to the sea from the Malecón, late, in the silence of the night. We kissed and said our good-byes. I went walking off toward home, carrying the bag. Slowly. I felt good. And I kept on slowly,

without looking back.

©Pedro Juan Gutiérrez